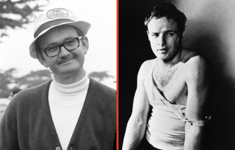

Marlon Brando stops by for a barbecue

The following is an excerpt from First to Leave the Party: My Life with Ordinary People…Who Happen to be Famous by Salah Bachir, available now in hardcover and ebook format from Signal Books.

“What can I get you?” my mother asked Marlon Brando. She wasn’t exactly clear on who he was, other than being some kind of actor and a new friend I had brought over for a backyard barbecue.

What could she get him? She would have asked the same of anyone. In our family and in our Lebanese culture, one of the ways we show love is with food. A lot of it. Lots of love, lots of food.

It wouldn’t have mattered if my mother had known who Marlon was, because she treated everyone with the same courtesy and hospitality—and anyway, to my mom, her kids were the stars. No one shone brighter. Whether I brought over Ginger Rogers, Douglas Fairbanks Jr., Elizabeth Taylor, Ella Fitzgerald, or any of the celebrities I befriended over the years, to her I was always the main attraction. The only time I shared the spotlight was when one of my siblings or their kids were also on hand.

True, my mother didn’t bring out the good china for Brando; but then, she never used her good china with anyone, no matter how exalted. She had it there on display in the dining room buffet, one of those grand wooden pieces of furniture crafted in the old style, but I never saw her use it. She had a set of everyday china, a set of “better” china, and the “good” stuff that never saw the light of day. The homemade food was the main attraction, not the plates.

Marlon sat near the picnic table on one of our folding lawn chairs (the tubular metal variety with a fabric-strip seat), the pear and peach trees on one side and a wall of flowers on the other, with vegetables growing to disguise the chain-link fence that separated our house from its neighbor.

Our vegetables were heavy on tomatoes, Lebanese cucumber, and kousa—similar to zucchini and also known as Lebanese squash. There was also plenty of marjoram, sumac, and the summer savories one can eat green or add to salads, and when dried go into za’atar, a Lebanese spice blend that is suddenly all the rage everywhere but has been here all along.

Ours was a regular three-bedroom house—with a carport, behind a strip mall, on a dead-end street that connected to another little circle—in a working-class neighborhood in north Toronto called Rexdale. At the end of the street was the Humber River, where my two sisters and two brothers and I played out our Tom Sawyer adventures. There was a cedar hedge alongside the house and a big shed out back where Dad kept his tools.

My father knew Brando from On the Waterfront, but perhaps he was unaware of the stature of the man for whom he was pouring a glass of arak near the flowering fruit trees.

“Did you know that your name is English for the Lebanese name Maroun?” he asked Marlon.

“St. Maroun, yes! I love that,” exclaimed Marlon, to everyone’s amazement. “The patron saint of the Maronite Church.”

It was not the first time Marlon surprised me by coming out with something seemingly obscure, but he was a sponge for information that intrigued him. And virtually everything intrigued him.

“We’re not Maronites, we’re Greek Orthodox,” my father clarified over tabouli and fattoush salads.

“We’re not here to talk religion,” I interceded, heading that off.

I don’t think my parents would have acted any differently had they known their guest was one of the most revered actors of all time, a two-time Oscar winner for On the Waterfront and The Godfather—not that I put much stock in awards. Who’s to say who is “the best” of anything? We were all instantly in love with Marlon anyway. He put everyone at ease and tasted everything Mom made, complimenting her lavishly. A couple of times he asked, in French, for the names of certain foods in Arabic.

It seemed that Brando was up for just about any conversation, no topic off limits, but I purposely steered the talk away from his fame and acting career. It’s all on screen anyway, and I figured he’d enjoy a break from the endless questions—what was it like doing this or that or with this one or that one.

I also had no need to ferret out his secrets, sexual or otherwise. In the end, though, he learned all about mine.

It had always been Brando for me. He was one of the most exciting film actors to watch. I had heard Elizabeth Taylor say that everyone who met him, male or female, straight or not, felt the attraction. And in many cases, Marlon was up for it: from Laurence Olivier, Richard Pryor, and James Dean to Marilyn Monroe and Rita Moreno—just a few of the names linked to him over the years.

Playwright Arthur Miller wrote that when Brando appeared in A Streetcar Named Desire on Broadway in December 1947, “it caused such a sensation that he seemed like a tiger on the loose. A sexual terrorist. Brando was the brute who bore the truth.” At the moment, the brute was in my childhood backyard in Rexdale, slouching and talking horse racing and cards with my dad, eating my mom’s homemade mamoul and fruit jams for dessert, calling them Mr. and Mrs. Bachir.

Brando famously did not do interviews, but Fritz Friedman, then the head of publicity at Columbia Tristar Home Video, had called to tell me it was an outside possibility that I could have Matthew Broderick for the cover of Premiere—the Canadian home video magazine I published—if I visited the set of the new movie the two were filming, The Freshman. In that 1990 comedy, Broderick plays a strapped New York City film school student who takes a job with mobster Jimmy the Toucan smuggling a rare Komodo dragon hither and yon. The running gag is that Jimmy the Toucan bears a suspicious resemblance to Brando’s mob boss Vito Corleone.

For The Freshman, Brando played a Mafia chieftain. A selection of Asian water monitors stood in to play the supposed Komodo dragon that Broderick lugged around for the majority of the movie.

Fritz told me with regret that I would have to get myself somehow to this unknown, misbegotten corner of Toronto where the movie was filming—maybe I could look it up on a map—called Rexdale.

Rexdale!

That’s where I had grown up from the age of ten, when my family first came to Canada. It was where as a teen I’d held a succession of summer jobs that will sound familiar to most youths who grew up around there at around that time. I worked several part-time gigs after school and in the summer at one of the three area warehouses of Simpsons-Sears, a partnership between the Canadian department store Simpsons and the American behemoth Sears.

The factory was on Rexdale Boulevard, and I was in what they called Department 42, which sounds like one of those government-suppressed UFO enclosures but was something much more mundane—it was where they repackaged the stuff that came back, like toilets and bathtubs and hardware items.

I also worked on the potato chip conveyor line at Humpty Dumpty and spent one summer at Labatt Breweries. After those experiences, I lost all desire for chips and beer.

The Freshman would go on to shoot at several locations dear to my heart—including a particular gas station, now a Petro-Canada, where the Komodo dragon breaks loose; the Woodbine Centre mall on Rexdale Boulevard, where I often dropped my mom to go shopping and where in the movie the creature swims with the bumper boats at the indoor Fantasy Fair amusement park; near the Woodbine Racetrack, which my dad frequented a little too often and where the Royal Family regularly attended the annual Queen’s Plate—the oldest continuously run horse race in North America, funded in 1860 with the blessing of Queen Victoria; and at the Weston Arena, where I played goalie in hockey and lacrosse, and where Marlon was unhappily and unsteadily learning to ice skate for his role.

With my meeting with Broderick secured, I then used every contact I had, called in every chip, to get some face time with Marlon, too. The interview with Matthew never actually happened, but something better did: Marlon and I hit it off right away and we began spending time together. Like friends.

I know, it sounds ridiculous. Me, friends with Brando? I don’t think so. Who was I to be palling around with him?

When I first met him, I approached it almost like a date. There was a nervous sexual energy to it, like when you’re going out with someone new. Although it wasn’t romantic, it felt the same, that anxiety you get when you don’t want to screw things up or overstep your welcome. I didn’t want to blurt out, “Hey, Marlon, how ya doing?” as if we were childhood pals.

I took care not to commandeer too much of his time—and he later gave me sh*t for it! Every couple of weeks, I’d receive an unsigned gift from a shop not far from the hotel where Brando was staying. One time, my mystery gift-giver sent a letter opener with a bluebird of happiness on it made by the Danish designer Georg Jensen. Another time he sent a Steuben candy dish. When I called Marlon to thank him, he’d lace into me: Why hadn’t I called to see if he was free?

It was also, frankly, easier for him to dine out and relax when he was with me, because if he paid for dinner with a credit card in his name, that would mark the end of whatever blissful anonymity he might enjoy for the rest of the evening. I always gave my credit card on the way into the restaurant so Marlon wouldn’t have to pay and thereby reveal his identity.

As we went around together, I always introduced him as my cousin. At some of these places I received preferential treat- ment—as I was well known in those parts, and this big guy was simply “cousin George from Lebanon.” On a couple of occasions, people said, “Yes, I can see the resemblance”—because at the time I did look some- what like him, enough so that friends who later saw the skating scenes in The Freshman would swear it was me. Except that I’m a good skater. Marlon and I even joked that I could serve as his stunt double. Maybe it wasn’t a joke, because Marlon, although he made a valiant effort, really could not skate at all.

From the moment I met him, we talked about everything—politics, olive oil, Indigenous rights, Lebanon . . . the guy was a walking encyclopedia, and not just of dry, lifeless information, but of limitless curiosity and a deep appreciation for things you would never guess he’d heard of.

He was familiar with Indigenous Canadian painters. He had a keen appraiser’s eye for sculpture. So that I wouldn’t embarrass myself, I nervously boned up on Canadian art the night before I took him to art galleries. Luckily, I knew the director at one, and he walked us through the galleries showcasing landscape art of the Group of Seven; they, more than other artists, are how the world identifies Canada. At the end of the tour, the director said, “I hope your cousin George enjoyed his trip here.”

Marlon and I wound up having many talks and dinners while he was making The Freshman. I took him to my favorite restaurants, and a few times to an Indian buffet in Rexdale. When I mentioned there was a gay village in Toronto, he was keen to see it.

“Is there any particular bar you like?” he asked.

I didn’t really go to bars or strip clubs; they were depressing last resorts. But I took him to a coffee house frequented by bears—larger-sized gay men—on Church Street in the village for coffee, and another time for lunch. We sat outside on the patio, where people dropped by our table to say hi to my cousin George.

Friends of mine who knew it wasn’t actually a cousin I was showing around my hometown often wanted to know one thing—what was Marlon Brando really like? Well, he was charming and engaging, as you might expect. But who is to say what any of us is really like? People can spend nearly a lifetime with a person, either in friendship or marriage, and one day wake up to realize they never really knew them. You know, they were double agents or axe murderers, that kind of thing.

The question of what anyone is “really” like is a double-edged sword. I mean, what is each of us bringing to the table? Are we engaging enough that we bring out the best qualities in others? Are we late or do we come unprepared and then blame a lackluster meeting on the other person? What false expectations do we bring that we then feel are unmet, through no fault of the other?

The real question wasn’t what Marlon Brando the famous actor was like. It was about who he was as a person, not as a function of his day job or weight fluctuations or sexual history or reputation on the set.

Brando was a person who somehow invited others to confide. I learned more about myself even as I was learning a little about Marlon. It’s weird, but sometimes there’s a sense that you’d tell a stranger something you wouldn’t tell your closest friend, and I found myself opening up to Marlon about body image.

“I thought I looked too pretty as a young man,” I admitted to him. “I think subconsciously I put on weight to feel uglier to people.”

In the eighties, I was afraid of contracting AIDS and almost wel- comed rejection. Some of my eventual weight gain was about looking less desirable. Also, I had been sexually assaulted previously, and had also experienced a few uninvited incidents in a doctor’s office and at the barber. I still find it awkward when someone takes my blood pressure, and I can’t have a barber put a hot towel on my face to trim my beard. It’s hard for me even to sleep alone in a house.

Marlon clearly understood when I told him how I had packed on weight as a kind of counterbalance to the dangers of the AIDS crisis—the fear that I would get into trouble if I remained too attractive to other men, if I happened to go someplace where I didn’t have control. Weight can be a protective device. He and I had this in common; we had both been in great shape at one point.

Marlon’s weight famously ballooned over time, and it cost him in his career. He wanted to do a lot more, but Hollywood no longer offered him the good parts. Here he was, considered one of the finest actors of his generation, and he couldn’t get work because of his size! Like with so many of us in the world, the powers that be judged him by the pound. It was the same for Orson Welles and Elizabeth Taylor. Size became a source of huge rage for Marlon; he hated how people chose to define him in a way he could not change or control.

He asked a lot of questions about when I’d realized I was attracted to men. Was I totally gay? What about the woman I’d once been engaged to? I explained how that engagement had been more about my desire to have children. Also, the woman really was a lot of fun, and I genuinely loved her. He got this. He seemed to love the sense of family he saw in my childhood home—our unquestioned closeness.

My siblings and I all stayed in Toronto, even once we were old enough and motivated enough to leave. When I had a major job offer in Los Angeles, I turned it down. “We didn’t leave our land and homes in Lebanon and come here and learn a different language and do all those things just so one of you could leave,” my mom said; I took this as common sense wisdom, not a threat. At one point, Mom and four of her five grown kids even lived in the same apartment building.

“How did they feel about you being gay?” asked Marlon.

“In a way, it was touching. My dad said, ‘Don’t tell your mom, she won’t get it.’ And when I admitted I’d already told her, he laughed. ‘Why would you tell your mother first? I’m your best friend!’”

As for how my mother took the news, she told me: “All I want for you is to be able to have a child who has been half as nice to you as you have been to us.”

When Marlon came for lunch in our backyard, my mom served him the same wide-ranging Lebanese menu she would have served any guest. In addition to barbecued chicken, there was kafta with ground beef, onions, parsley, and sumac. There were shish kebabs with barbecued onions, peppers, and vegetables. She brought out endless platters of her homemade specialties: pita bread along with apricot, quince, and fig jams, the figs all the way from Lebanon.

And good luck being vegetarian—which I was at the time—around a Lebanese family determined to feed you. There is always a selection of meats, because vegetables-only is a sign you can’t afford stuff, so you never deprive a guest of meat.

Nevertheless, it was time for Mom’s homemade mamoul, a pastry made with dates, walnuts, or pistachios. She also put out a platter of kaak, a sesame seed–encrusted cookie.

I told Marlon about publishing Videomania magazine in the basement of my brother George’s store, and how things were so touch-and-go with that venture for a while that I’d moved back home to my parents’ basement. My mother had saved up a bunch of money and hired a gay designer to do the bathroom down there for me.

“Show me,” said Marlon, eager to see.

Marlon was incredibly supportive in a lot of ways. I was his equal— because he made me feel that way. Sure, I had heard about him sleeping with men and women, about his sexual prowess, about his physical endowment. I knew that he had slept with James Baldwin and Marvin Gaye… but I didn’t want to go there.

In a 1976 interview, the actor told a French journalist: “Homosexuality is so much in fashion it no longer makes news. Like a large number of men, I, too, have had homosexual experiences, and I am not ashamed.”

I think if it were not for AIDS, perhaps men elsewhere in the world might have become like many European and Middle Eastern men who, though not gay, have flings with other men. Not that it didn’t cross my mind that something could happen with Brando.

Brando was still hot in many ways, but more in the sense of how he had sturdy principles and was interested in and knowledgeable about so much. He could talk Indigenous art with my friend the museum director. Civil rights with activists. Horse racing with my dad. He was an olive oil aficionado and loved the special brand from my family groves, as well as the story about the Phoenicians delivering olive trees around the Mediterranean. He was eager to talk politics and Palestinian refugees.

That’s why I get so furious with people who claim he was some kind of monster. To me, he just wanted to learn about everything. I think if he wasn’t challenged, he’d get bored and kind of dismiss people, and those people who couldn’t keep up with him would turn around and trash him, personally and professionally.

They did it to recover their sense that they were all that, when Marlon probably knew they weren’t. They did it to promote themselves by putting down someone more famous. So, you’re just some two-bit actor and you were on a set with Marlon Brando and you think he was mean to you? That’s your story to tell now? Instead of telling of your own achievements? I could mention names—the actors who rode on Brando’s coattails in this sick, negative way—but why give them a shred of publicity?

Looking back now, I realize that Brando came into my life at a time of great uncertainty for me. There was AIDS and people dying. There was a stigma around being gay, and people were being fired or shunned for it. I still needed to find my voice and my confidence, and here was this icon of the twentieth century who was also struggling with body image and his place in the world, telling me he thought I was handsome no matter what size.

Over the years, I lost touch with Marlon. But one time, when I knew I’d be heading to L.A., I called and asked if he would be free for lunch, and brought him an Inuit soapstone sculpture of a bear, similar to the pieces we’d seen together at a gallery in Toronto.

“I missed you,” he said. “Why didn’t you stay in touch?”

But you are Marlon Brando, I wanted to say! What could Marlon Brando possibly want with me?

It occurred to me that maybe it wasn’t just my parents who didn’t know who Marlon Brando really was.

First to Leave the Party: My Life with Ordinary People…Who Happen to be Famous by Salah Bachir, available now in hardcover and ebook format from Signal Books.

Related:

This article includes links that may result in a small affiliate share for purchased products, which helps support independent LGBTQ+ media.